Rock Hudson was one of the most popular stars of the Golden Era of Hollywood. At the height of his fame he starred in some of the most iconic films of the 1950s including the box office smash, George Stevens‘ Giant with Elizabeth Taylor, and James Dean, Hudson was nominated for best actor for his work. He was a favorite of auteur Douglas Sirk and starred in three of his timeless films, Magnificent Obsession, All That Heaven Allows, and The Tarnished Angels.

While he never reached those heights again, he did consistently work regularly throughout his career and still delivered the occasional hit like Pillow Talk and memorable “ahead of its time” films like John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, which some believe to be his best performance.

In the 1980s, in the twilight of his career, rumors started to percolate about his sexuality, a longstanding masculine stoic figure, many dismissed these as false whispers. When it was publicly disclosed that he had AIDS, he became fodder for the gossip columnists while the disease itself was still unknown to the public at large, making him a mystery to the fans that thought they knew him. He died not long after and he was the first major public figure to have the disease. Ultimately, his visibility as a famous actor led not only to increased funding and research, it also humanized the illness to the general public who still were fond of Hudson.

Stephen Kijak has been a prolific documentarian for over two decades, having directed indelible films like Cinemania - documenting the exploits of obsessive moviegoers, Scott Walker: 30th Century Man - which profiled the legendary singer and Stones in Exile about the making of The Rolling Stones classic, Exile on Main Street, among other memorable films. Kijak’s most recent film is about Rock Hudson and his dual life as a hyper-macho movie star and his private life in the closet during the super-conservative 1950s. Kijak recently spoke to Immersive via Zoom.

[Note: The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.]

So what propelled you into the world of Rock Hudson for this film?

It was brought to me by some producing partners of mine, somewhat developed already with a very specific focus on the eighties and the AIDS crisis and I just thought it was an important story to tell and it was just great material. It had mostly archival elements, the scope of Hollywood history, and a great cross-section of stories from the eighties explaining and centering the AIDS crisis at that moment.

What was there stuff that you didn’t know or that was surprising, did anybody anything leap off the page while researching?

I’ve got to admit, I didn’t know a huge amount. I feel like I was more interested in the filmmakers he worked with than him as an actor, to be honest. I love the Sirk movies. John Frankenheimer’s Seconds is amazing, but I think I was more aware of them in the context of those directors’ bodies of work. I maybe wasn’t aware of the scope of the career. There are over 60 movies. It’s extraordinary.

What was amazing was to rely on the biography by Mark Griffin, “All that Heaven Allows.” He became an invaluable partner in doing this and framing the story in understanding the scope of Rock’s life, we got off easy. I mean, he wrote this brilliant book. The research was there. Then of course, we did a lot of our own, reading all the different biographies and looking at all these different perspectives, and they all tell different stories.

Through the lens of history, now we can look at Rock Hudson clearly as a gay man living in the closet in the 1950s, which was a very conservative time in America, and somehow, he always seemed chill and relaxed.

Yeah, he does have that demeanor. It’s really interesting. Talking to the guys that knew him, I mean, there’s a line in the film where his friend down in Laguna was like, “Oh, that’s so him, he’s not even acting to change smoking.”He was just a laid-back, casual guy. I think he was at his best when he was supported by a director and he could relax into these roles and kind of be himself in a way, but you’ll never really know.

I mean, that’s what is fascinating about him from an acting perspective, he never really got the credit for being a good actor. He was always, the word is like, “Oh, he’s a great movie star. Maybe not the best actor.” And that might be true, but he developed a specific technique by coming of age in the studio system. That’s all his training, never learned how to act before being signed by Universal. So, there is that natural affect to him. And when it’s used properly, he is exceptional.

He was ironically considered a relic of the old order, the studio system…

Well, yeah, because he is already, what’s interesting is by the time you’ve hit 1959, and 1960 with the Doris Day movies, he’s already kind of considered a bit of a washed-up square. I don’t know if he was ever cool if that term applies but by the time you get Marlon Brando, and James Dean… Rock was not from New York, Rock was not Actors Studio. He was studio, studio. I think for movies, snobs would put him in a lower-class of actor in a way.

But he wasn’t part of the Vanguard. He wasn’t part of that new world. He was just primed right in the center of that studio system, conservative kind of ethic, and someone who wasn’t necessarily in control of the roles he took because he was a studio player, he had to do what he was told. Hence, all the kind of garbage movies that clutter his filmography. I mean, there’s stuff to enjoy in a lot of them, but there are some real duds, not necessarily his fault.

Can you talk a little bit about discovery in terms of finding images that match scenes? Because there wasn’t just the eclipse or also these great archival photos of him.

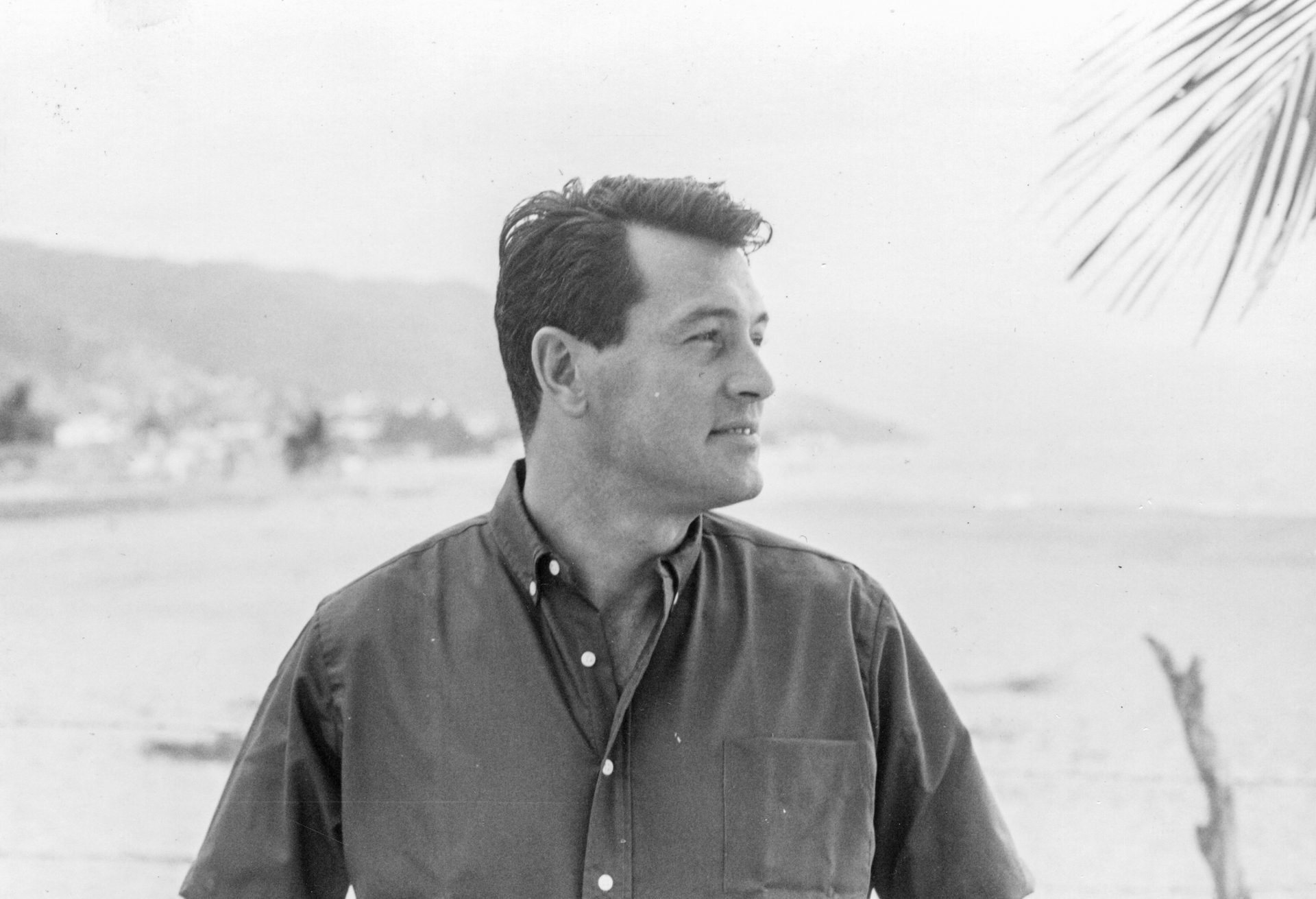

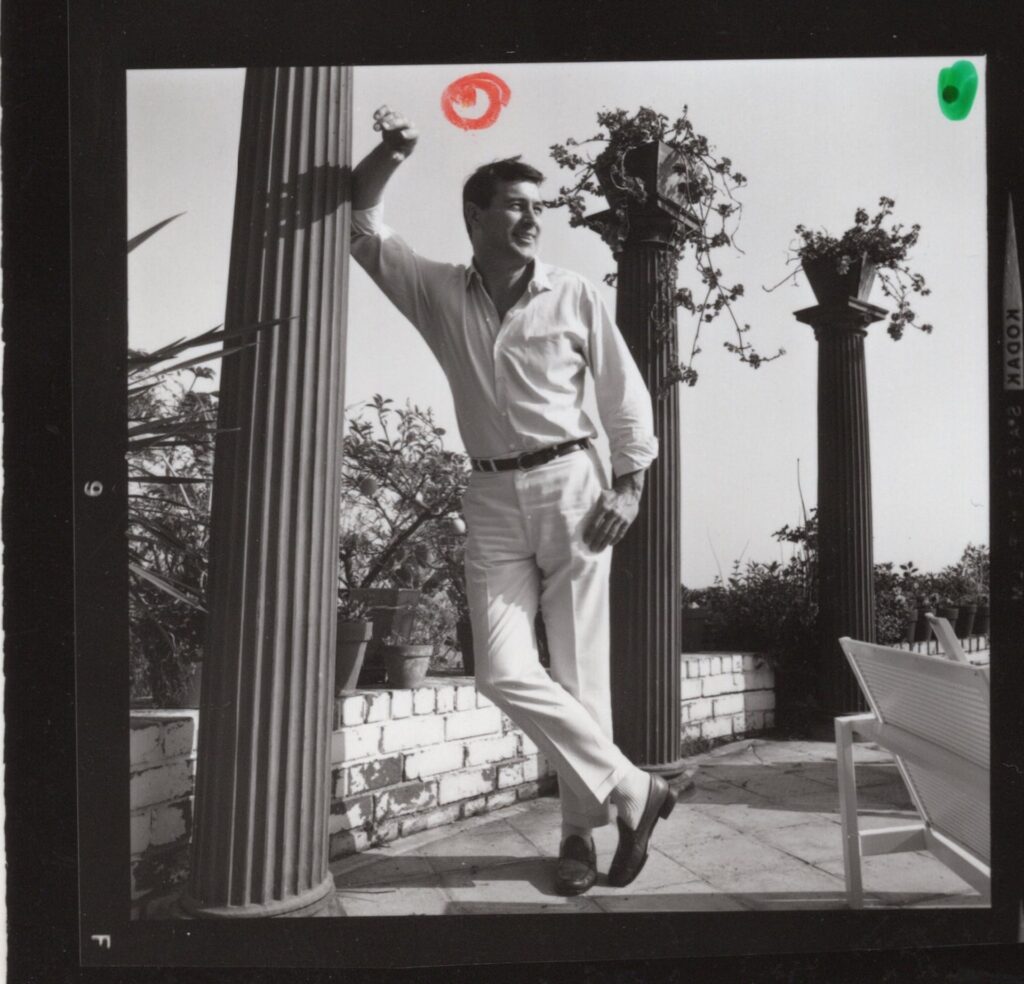

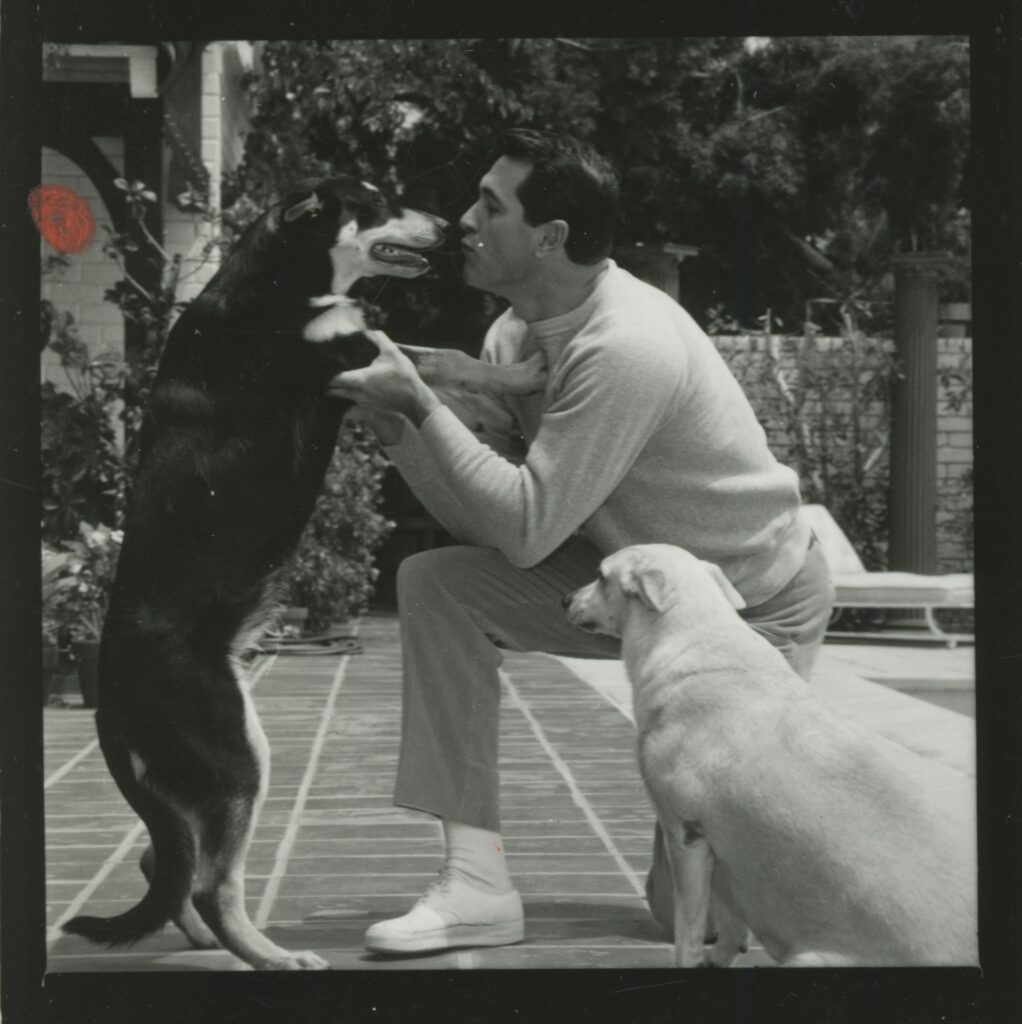

The estate collection is a collection that was preserved on nice, organized shelves, and binders full of photographs. Every movie had a binder. There were binders labeled personal. There were binders labeled Childhood, Army, and Navy. I have a great archival producer, Adele Sparks, who used to work at a studio, so she knows very well where the Hollywood stuff is buried and various archives. He was an extremely well-photographed celebrity, and we found all the personal photographs and we had stacks of magazines from the period, so he was on tons of covers and there’s so many stories, it was just so much to work with.

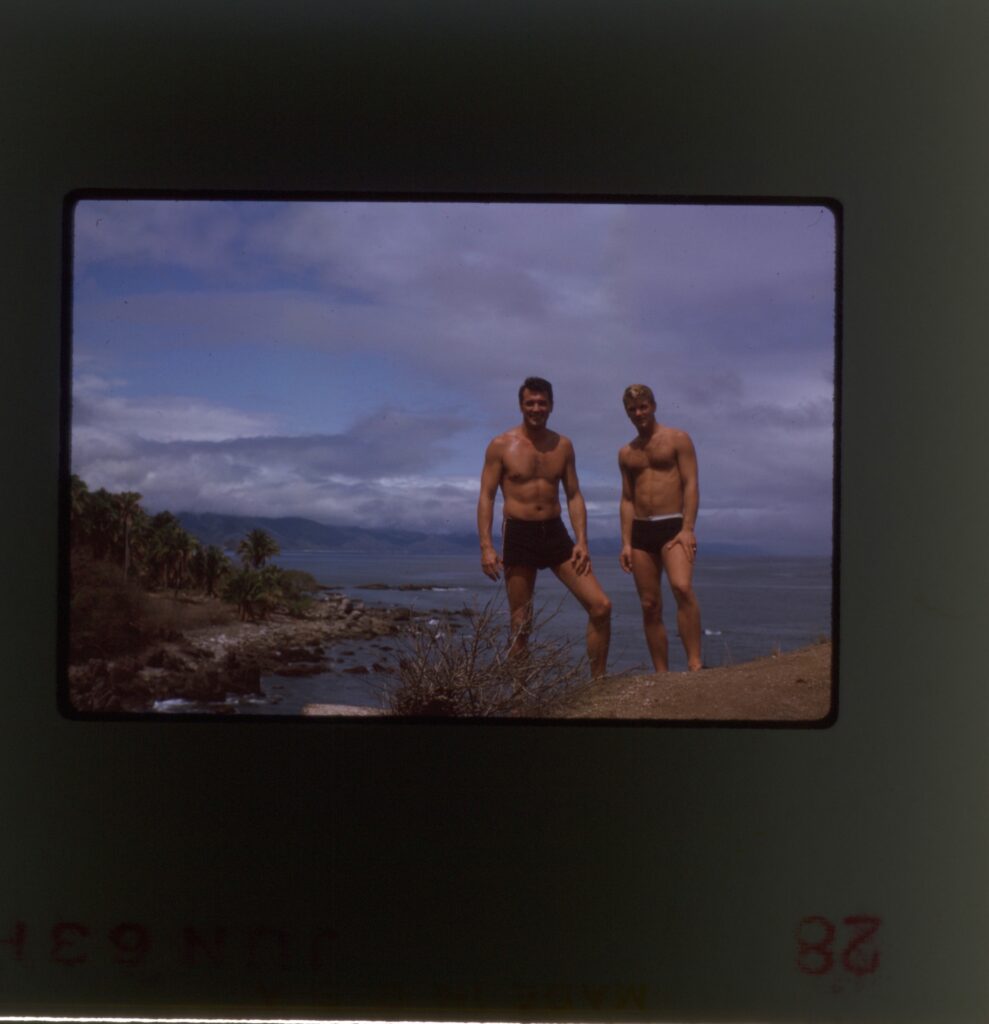

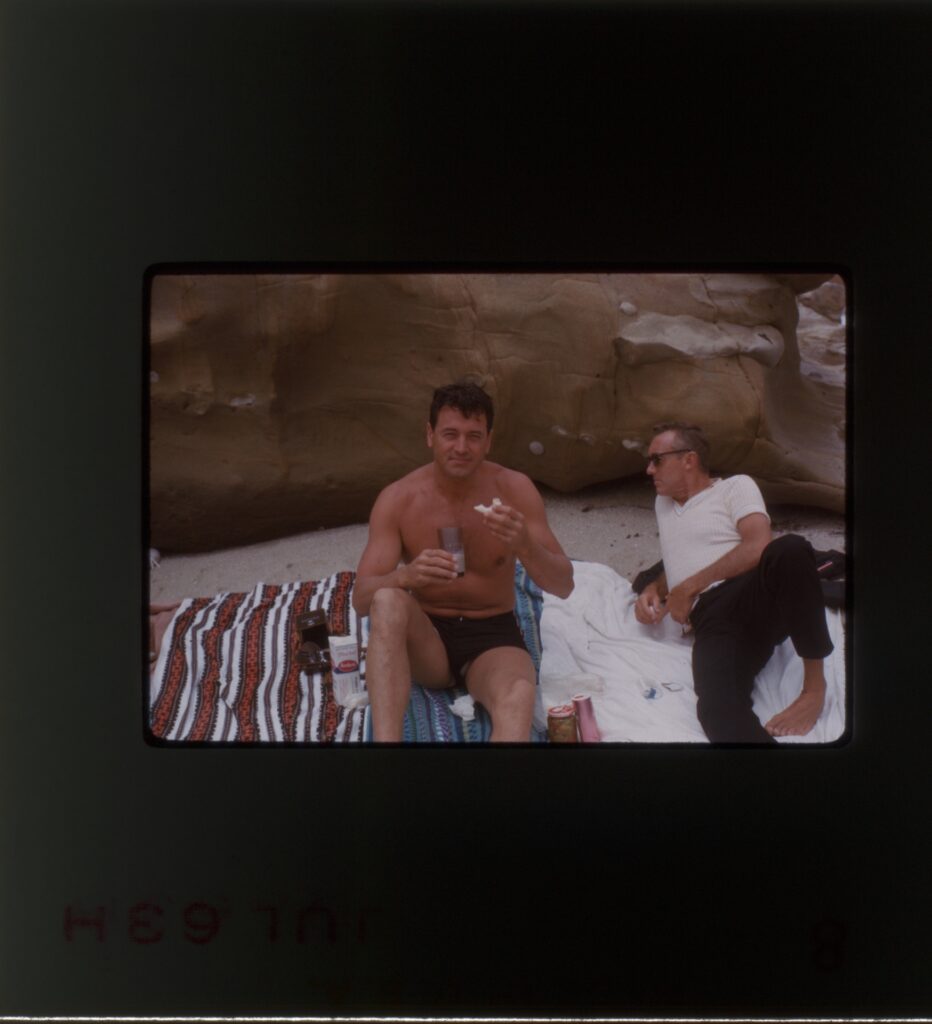

Me and my producer, Carolyn Jurriaans, and we would just have a scanner, we’ll travel, we just do it all ourselves. We’ve scanned thousands of images and slides that we found, the biggest score for us, was uncovering that one photograph of Rock and Lee Garlington, his boyfriend in 1963, in their baiting suits on a cliff that Lee didn’t think existed.

What were your interview setups like? Over what kind of period did you shoot?

There weren’t a lot. We didn’t shoot a lot of stuff. Honestly, it’s hard to even remember. I mean, they were in a relatively compressed period. We wanted to get it all in and get it done. I mean, we had a team in New Zealand interview Lee Garlington first because the poor man has since passed, and we’ve lost a couple of guys. Lee had had a stroke and his husband was determined for us to get in there and get him while he still could talk to us and remember things.

And then, the last thing we did was in the Poconos with Peter Kevoian, a lovely man, a Broadway actor, who was a famous singing telegram in Los Angeles for years. He was in a play with Rock when Rock started doing theater, and Rock helped him get cast on an episode of McMillan, his TV show. We lost Peter just a few months ago.

And we had a team in London sat down with Armistead Maupin who I interviewed over Zoom, which is always uncomfortable, but he was wonderful. It was done in a pretty compressed amount of time. We didn’t have a huge production budget, so the decision was made to just put these men on camera.

How long did the editing take?

I’m going to say 32 weeks but I have no sense of it. We edit and then they tell us we have to stop and we stop. It was some interviews and a lot of archival stuff. My editor, Claire Didier, who’s a genius, we’ve done several things together now. First, we had to watch 65 Rock Hudson movies and we did it. We do the work and we sat down and noted them all to death. And yeah, it was a good fast clip. It felt fast to me.

What do you hope that audiences take away from this different side of Rock Hudson?

It’s a historical corrective. It’s like, let’s remember that moment. I think it’s always important to look back, especially at the mid-eighties when we’re thinking about AIDS and the AIDS crisis. People just don’t remember it. If you’re of a certain age, it’s just ancient history. And if there’s a way that we can remind people, it’s great to wrap it up in this story of someone’s life, this double life that this man had to live, but also to reckon with a body of work that is a lot more significant than I think history has led us to believe was also important.

So, it’s just a big juicy package of history of Hollywood and AIDS and gay history and a really interesting slice of life with some real personal details. And it’s just an intimate telling and a real way to understand who he was and what he meant.

Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed is now available to stream on Max.